Mysterious symbols, strange creatures, and terrifying judgments make Revelation seem like a code that needs to be cracked. And for decades—maybe centuries—Christians have tried to do just that. Charts, timelines, conspiracy theories, and end-times calculators have all been used in the name of "figuring it out."

But what if that's not what Revelation is for?

What if we've been reading it with the wrong lens, asking the wrong questions, and using the wrong decoder? What if the key to understanding Revelation isn't hidden in the news headlines or some modern political theory but in Scripture itself and the historical and literary world of the first-century Church?

Revelation Was Clear to Its First Readers

One of the most important principles of biblical interpretation is this: the Bible was written for us, but not to us. That's especially true with Revelation.

John didn't write this vision as an abstract spiritual message to be decoded by future generations. He wrote to seven churches in Asia Minor, which were living under the shadow of the Roman Empire. They were struggling with persecution, tempted by compromise, and uncertain about how to remain faithful. John knew them. He addressed them by name. And he expected them to understand what he wrote.

That alone should shape how we read this book. Too often, we come to Revelation asking the wrong kinds of questions—questions like:

What current event does this symbol represent?

Which nation is this prophecy about?

When will these things happen in our time?

But those are not the questions the original audience would have asked. But we often misread Revelation (and most of Scripture, actually) because we bring our own expectations and baggage to the text. This is where the difference between exegesis and eisegesis becomes critical:

Exegesis means drawing meaning out of the text. It asks, "What did this mean to the original audience? What does the text say, in its context?"

Eisegesis means reading our own ideas into the text. It asks, "What does this mean to me?"—but not in a good way. It skips past the original meaning and imposes our own assumptions.

And then there's narcigesis—a popular but dangerous trend that makes every passage about the reader. It turns Revelation into a book about our fears, our nation, and our political enemies. Instead of asking what it says about Christ and the Church, we make it about us.

But the truth is that Revelation made perfect sense to the people John wrote it to. That doesn't mean it's simple; it's a rich, layered, symbolic letter. But it means we're not meant to decode it like a secret message containing the signs that 21st-century Christians should look for to expect the Second Coming. We're meant to enter the world of the text: to understand the symbols, the Old Testament allusions, the Roman imperial context, and the call to endurance that anchored those first believers.

If we don't start there, we won't end up anywhere helpful. The right question isn't, "What does this beast symbolize in 2025?" but, "What did John's readers understand the beast to be and how does that help us remain faithful today?"

There's Nothing New in Revelation

One of the most overlooked truths about Revelation is that there is really nothing mysterious about the message. There's nothing in this book that hasn't already been taught elsewhere in Scripture. Instead, Revelation pulls back the curtain on what has always been true and paints it in bold, symbolic, and apocalyptic colors.

Every major theme in Revelation has deep roots in the rest of the Bible:

God judges evil with justice and mercy (Genesis to the Prophets)

God calls His people to faithfulness in the face of persecution (Daniel, Acts, the Epistles)

Jesus reigns as the slain-yet-victorious Lamb (the Gospels and Hebrews)

New creation follows judgment, not destruction (Isaiah 65–66, Romans 8, 2 Peter 3)

This is especially important to remember because some people treat Revelation as if it has its own separate system of theology based more on speculation than on Scripture.

But Revelation is not a theological outlier. It's the climax of the biblical story. The more familiar we are with the rest of Scripture, the less confused we'll be. Revelation doesn't break new ground; it unveils the ground we've already been walking on all along.

It's Not Chronological

One of the biggest mistakes readers make with Revelation is trying to read it as a timeline—chapter by chapter, event by event—as if it were predicting a strict, step-by-step sequence of future events. But Revelation isn't laid out like a linear narrative. It's cyclical. It shows us the same spiritual truths from different angles—through visions that overlap, echo, and intensify as the book unfolds.

This approach is called recapitulation, and it's not just a scholarly theory—it's the way apocalyptic literature works. Revelation is filled with repeating patterns:

Judgments come in sets of seven: seals, trumpets, and bowls.

Each cycle ends in some form of cosmic upheaval or final judgment.

The vision resets and zooms in from a different perspective.

Trying to line these up as a single timeline leads to confusion and contradiction. For example:

Does the world end three times?

Are there three separate judgments of the earth?

Is Satan bound once, twice, or not at all?

But if we read the visions as parallel cycles retelling the same story of conflict, judgment, and victory from different angles, it all begins to make sense. If we approach Revelation as a strict timeline, we'll get frustrated and lost. But if we recognize its structure as layered, symbolic, and thematic, we'll be equipped to understand the message that's been there all along: stay faithful because the Lamb wins.

Numbers Have Meaning

One of the clearest signals that Revelation is symbolic is its use of numbers. And here's the key point up front: No number in Revelation is meant to be taken literally. Not a single one of them.

The biblical world didn't use numbers the way we do. In Scripture, numbers often carry spiritual, covenantal, or symbolic weight. Revelation leans heavily on that tradition, drawing primarily from the Old Testament, where numbers were used to express divine completeness, imperfection, or covenant identity.

Here are some of the most important examples:

7 – Symbolizes completeness, fullness, or perfection. Think of the seven days of creation or the seven spirits of God. In Revelation, there are seven churches, seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls, each representing a complete, divinely ordered reality.

6 – The number that falls short of 7. It represents human incompleteness, imperfection, and rebellion. That's why the number of the Beast is 666, a grotesque intensification of failure. It's not a barcode, microchip, or vaccine. It's a warning about what happens when humanity tries to be God and falls painfully short.

12 – The number of God's people: 12 tribes, 12 apostles, 24 elders (12 + 12), and the 144,000—which is 12 × 12 × 1,000. It's a symbolic picture of the complete people of God, sealed and secure.

1,000 – Used to express vastness or completeness. "A day is like a thousand years" isn't meant to mark a calendar—it's meant to show scale. When Revelation talks about a "thousand years," it's not about duration. It's about divine authority and the fullness of time.

3½ years / 42 months / 1,260 days – All the same length of time, and all rooted in Daniel's prophecy, symbolizing a limited time of tribulation and persecution.

If you try to take these numbers literally, you'll almost always end up in the weeds. But when you read them symbolically, as the first readers did, they unlock deep theological meaning:

God's purposes are complete.

Human kingdoms are flawed and doomed.

God's people are known, sealed, and protected.

Tribulation is real but temporary.

Understanding this will keep us from speculation and help us listen for what Revelation is really saying: trust the God who numbers His people; He knows what He's doing.

Symbols Must Be Read in Context

Revelation is filled with powerful and sometimes strange imagery: beasts, scrolls, lampstands, dragons, and a slain Lamb who reigns from a throne. The mistake many modern readers make is trying to interpret these symbols using contemporary categories, turning beasts into politicians, marks into microchips, and plagues into pandemics.

But the original audience didn't think in those terms. They were steeped in the imagery of Daniel, Ezekiel, Zechariah, and the Psalms. John didn't create a new symbolic universe; he re-applied existing biblical language to their present moment through the lens of Jesus Christ.

The right question, then, is not "What could this mean today?" but "Where have we seen this before in Scripture?" When we let the Bible interpret itself, the images in Revelation begin to speak with clarity. The Lamb echoes the Passover sacrifice and Isaiah's suffering servant. The sea beast draws on the ancient motif of the chaos monster from Job. The lampstands represent God's people, just as they did in Zechariah. Symbols in Revelation are consistent, theological, and deeply rooted in the story of God's covenant with His people.

If we want to understand Revelation's message, we must be willing to do the work of tracing these symbols back to their source. When we read them in context, the book becomes less confusing.

A Better Way to Read Revelation (and the Bible)

Revelation doesn't require a secret code or a prophetic algorithm. It requires patience, humility, and a willingness to read it the way John intended it to be read; through the lens of Scripture, with an awareness of history, and with the heart of a disciple.

It's not a puzzle; it's a portrait. A vision of what it means to remain loyal to Jesus in a world full of counterfeit thrones, seductive powers, and constant pressure to compromise.

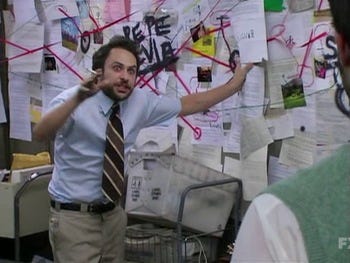

The first-century Christians didn't lock themselves in a room looking for Pepe Silvia.

They needed encouragement to hold fast, clarity to see through deception, and hope that their suffering wasn't in vain. That's exactly what John's letter gave them, and that's exactly what it still offers today.

When we stop trying to make it about us—our nation, our timeline, our fears—and start letting the text speak for itself in its own context, something beautiful happens. The strange becomes meaningful, and the terrifying becomes hopeful.

A better decoder isn't a new tool or theory. It's a posture of humility: the willingness to listen well, study intensely, and follow faithfully.